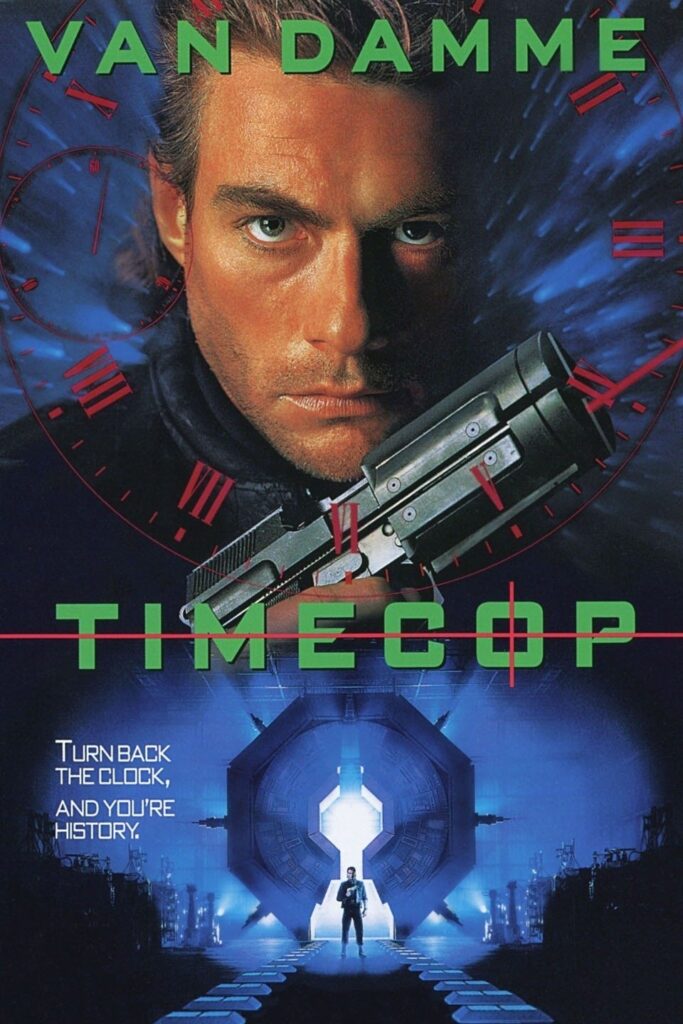

Timecop. It’s fantastic, incredible, bordering on genius. Such a magnificent achievement.

Not the film. The film is a fun, quite silly mid-90s action romp with Jean Claude van Damme. It has all sorts of strange plot lurches, barely sketched in characters and a story world that looks like it might be making up the rules as it goes.

No, I’m talking about the TITLE. That title is amazing. Just seven letters but it transmits so, so much information about the film. Let’s look at it for a minute.

TIMECOP.

We know immediately that it’s a science fiction film about time travel. Has to be. It’s ‘time’ something. What if we saw a film called ‘Time Badger’? Or ‘The Time Phone’? ‘Melvin and the Time Shoes’? We know they have to be movies that revolve around time travel. It’s right there in the title.

But here the title sounds like a person, they’re A time cop. Surely they have to be the protagonist, and surely they’re involved in the policing of time. So we know there’s going to be police-procedural-style action, piecing together clues. And the mere fact that there’s time POLICE implies that there must be time CRIME. So just from the title we can see that the film will probably be dealing with specific crimes that could only occur using time travel – so already we’re guessing at insider trading, or murdering people before they do something important. And that’s necessarily going to lead to paradoxes, people meeting themselves, attempts to redo something that might have failed first time around. And finally, it’s not called TimePolice, it’s TimeCOP, so we know the lead is going to be a blue collar kind of police officer, not some by-the-rules guy in a suit. There’s probably going to be some rough stuff, bending the law to do the right thing, and very likely some punching and shooting.

And yes, every single one of those things appears in the movie. Perfect.

It’s such a win when you can get the whole idea of your movie across in the title. I’ve only gotten close once, with a script I wrote a few years ago. It’s a comedy about a spy whose department gets its funding axed after a particularly lavish mission goes wrong. The spy has to finish his assignment and bring the villain to justice while spending no money whatsoever. The film is called ‘Free Agent’. A couple of people accused me of writing the title first and then coming up with the story afterwards, but no, I wrote the entire first draft before I realised what the title should be. And I still think it’s pretty cute.

But it’s no Timecop. THAT’s a title I envy.